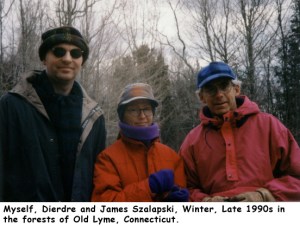

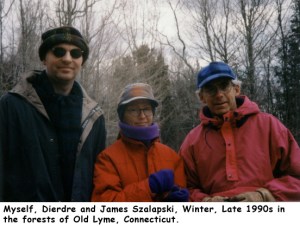

I met James almost 20 years after he made Heartworn Highways. He came into an edit studio I was working at to cut a trailer of an independent film he had shot. We became friends pretty quickly, finding that we were interested in the same kind of things – telling stories, wrestling with technology, UFOs and government conspiracies (which led us both the X Files). James was an accomplished cinematographer with one of the brightest and most inquisitive minds that I’ve ever met. He liked to problem-solve especially in story telling and the technical ways we communicate them. But James was also a pioneer who moved to New York City from Minnesota 10 years before I moved to New York City from Vermont (He was 10 years older than me). When he came to the city he found an empty and essentially forgotten PreSoHo and moved into an incredible loft space on Spring Street, struggling and ultimately watching the region transform around him.

James was a pioneer who became a friend and mentor – he made a lasting impression on anybody who met him by being continuously supportive and always interested in what you were doing.

Whether shooting a documentary for PBS one month or directing a film with Roy Schneider later in the year James would always welcome the opportunity to actually tackle a new production problem – he was eternally ready to jump into life. Which made it all the more difficult for everyone when he finally passed away after and on and off battle with cancer that finally caught him in September of 2000.

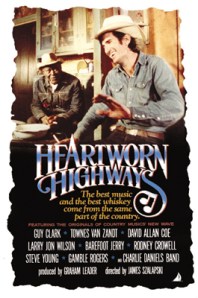

Heartworn Highways is the great achievement in the life of someone who did a lot of pretty excellent things. It’s an honest and compelling look at a musical culture that was very much in transformation in 1976 – and was fortunately documented by James Szalapski and his small crew of merry filmmakers.

The following is an interview I did with James Szalapski in 1996, which was transcribed and printed in the DVD booklet that comes with the DVD..

T. Campbell:

At the time the movie was shot, and right up until the time of its original release, the film was called ‘New Country’ but then something happened which made you look for a new title. Could you tell us about that?

J. Szalapski:

They came out with a yoghurt called ‘New Country’, right while we were cutting the movie and there was advertising everywhere … we don’t want people to think its a yoghurt movie, so we changed it to ‘Outlaw Country’ for a while because these guys where referred to mostly as “outlaws,” and tried to go for something more evocative, threw round a bunch of titles and this one came together like a feeling.

T. Campbell:

You mentioned that these guys were kind of, kind of outlaws and they broke off from Nashville… Can you give us some background on that?

J. Szalapski:

Well, by the early seventies Nashville had sort of become very rigid. All the songs were sounding the same, they just turned out product like crazy and they kept country music in a narrow defined range. But the young guys wanted to do something different. A lot of them had gone through the sixties and had experienced the whole explosion in rock and pop music and wanted open it up a little bit. “LA Freeway” is kind of an anthem for these guys; they went to places like LA and New York and, and discovered it wasn’t where they belonged. Their roots were in the South and they had an emotional connection to their grandparent’s generation there. But when they came back to Nashville and to Austin, Texas they brought back with them the electric guitars and the raw sound of their own generation. But the music they were making connected more to a generation older than the one in place in Nashville.

T. Campbell:

They looked to guys like Hank Williams …

J. Szalapski:

They where looking, back to them, and I found that very interesting, this generation jump which I tried to put in the film with some of the older characters in the film. Another thing that was happening was that there weren’t a lot of places to play music in Nashville – outside of recording studios. There were very few clubs there. But in Austin there was and Austin kinda became a new capital for this new music. Austin is a university town, very liberal, pretty advanced and there were a lot of clubs to play music in. It pretty quickly became like a rival to the main, established, “religion” there in Nashville.

T. Campbell:

I wanna get into how this film was made, but I’m curious that you talked about this group of people, these outlaws.

J. Szalapski:

My connection to all this was very personal and direct. The film is dedicated to Skinny Dennis. Dennis played stand-up bass around LA. And Guy Clark was in LA at that point, this was the late sixties. The movie opens with ‘”LA Freeway” which Guy wrote about LA and he mentions Skinny Dennis in the song, “Here’s to you ol’ Skinny Dennis…” Dennis rambled around and for a time came here to live with me in New York City in seventy-two or so. Guy had gone to Nashville so he went down to visit Guy, and suddenly he felt at home for the first time in his life. When he came back he told me about the scene there and I was at the point where I really wanted to make my own film and I thought maybe this could be an interesting subject. So I went down there and stayed with him and then just met the people that he knew, Guy and Townes Van Zandt. He dragged me over to see David Allan Coe who was kind of very different from them, more outrageous, you know. He’s like the biker. And Townes is the poet and Guy is like superb craftsman/writer …

T. Campbell:

…

He’s the one who repairs the guitar in Heartworn Highways?

J. Szalapski:

He also does that too, yes. Townes would be one of those people who wouldn’t do anything for a year and then sit down and write five songs in one night.

T. Campbell:

Dennis died before you made the film. Was there any forewarning of that?

J. Szalapski:

Well, Dennis had Marfan’s Syndrome. It’s a birth defect. Lincoln had it. And it causes your body to get very boney and elongate. Dennis was six foot seven and weighed 135 pounds that’s why they called him Skinny Dennis. The doctor said Dennis wasn’t gonna make it to his twenties, you know. And, he was a pretty hard partying guy, he didn’t walk around on tip-toes because of his heart problems. Eventually he did die of heart failure. He was twenty-nine. But back in the early seventies he introduced me to everybody in Nashville and Austin. I shot slides, I got copies of their music, most of the guys only had demo’s, they didn’t have albums at that stage. I took all that around and showed it to people to try to raise some money for the thing. And they said things like “Go and get Willie Nelson or Kris Kristofferson as a host for the film” and we’ll think about it, but nobody knows any of these people. But I wanted to go with the guys who were on the way up, I think they, they’ve got the most interesting energy, they’re the avant-garde on this thing that’s happening. So, finally, through George Carroll, I met Graham Leader in Paris who became the producer of the film. He was an art dealer in Europe.

The energy crisis had just hit and the bottom had fallen out of the art market. I played him the music and the music won him over. I also showed him some of my slides. So we went to Nashville and Graham financed what we felt was going to be an hour documentary for television. I think we had thirty-five thousand dollars. In about a month we had a small crew and were underway. We shot a couple of things the first day we were there, it was great, we were off to a running start, but then we didn’t do anything for four days. People’s schedules, cancellations, we just couldn’t get anything happening. The crew was getting grumpy… but then it took off. Way led to way and we started getting other people into it. I’d say it was about two weeks into it we felt we could make a feature film. So Graham he raised more money, basically over the phones and, and we finished shooting everything we could to make a feature. The whole thing took around four weeks.

T. Campbell:

How did the budget determine the style of the film-making?

J. Szalapski:

We went as lean as we could. Me and an assistant cameraman…My assistant cameraman on was also my assistant director, Phillip Schopper. We had worked together before and had become good friends. Phillip’s a very creative person with a lot of good and you want people around you who will keep you honest. Then when we got to the editing room he became the editor and I became his assistant editor. He was there at the Steenbeck doing all the cutting and I was finding stuff and looking over his shoulder.

And of course we would always confer about the editing with Graham Leader who stayed in New York for pretty much the whole course of the finishing the film. The grip was Mike Harris, Skinny Dennis’s best friend, who was then living in New York also. Larry Reibman was the gaffer. Larry was working for a film equipment rental house at the time and wanted to get out of the rental house and make movies. The sound man was very organic. He was great. Alvar Stugard was his name. Like I would walk into a situation and start looking around for how the light- ing falls and where the lamps are, what this is gonna look like. Alvar would walk around with his microphone and his headphones on, and test the acoustics of the room, and he would find the best sound might be over in the corner and he would say what sounds best for the place what really gives the feeling of place too, you know.

T. Campbell:

This is a technical question before we move on. What equipment did you use to shoot this film?

J. Szalapski:

A 16mm camera. About sixty per cent of the film was hand-held. I shot with an Eclair, French Eclair NPR, which is a difficult camera to use, it’s fairly heavy and the weight is about five inches in front of your chest, so you’re supporting it all with your hands.

T. Campbell:

Did you a use a Nagra stereo?

J. Szalapski:

Nagra stereo. We made a real effort to record everything in stereo.

T. Campbell:

Really?

J. Szalapski:

And the final result was mag stripe stereo, 35mm film with mag stripe on the side. Because this film was done before optical stereo, you know, the whole Dolby optical stereo thing that came into movies happened about two years after we finished the film.

T. Campbell:

So not only the music’s in stereo but the presence, the dialogue track the chickens and the lambs and whatever are in stereo on the soundtrack?

J. Szalapski:

Right, and we tried to get it as high fidelity as possible but we only had two tracks so when someone was singing and playing a guitar we put one mic on the singer and one on the guitar. Then in the mix we would put their voice in the centre, where it is on the screen pretty much, but we’d spread the highs and lows out according to the position of the guitar. If the guitar neck is up to the right, you’d put the highs up there and put the lows down at the body and so we’d have a stereo separation for the scene.

T. Campbell:

Is all of the music performed live?

J. Szalapski:

Yeah. Oh, yeah. You know, people played music, like you and I are talk- ing then a couple of other people would drop over and somebody would say “I’ve got a new song”, and they try out their songs and sing together and so it goes. There was a lot of drinking, these things would go till three, four, five, six in the morning. Eventually people would sort of lose the ability to sing very well, you know, but they could still play. Their body seemed to remember the guitar stuff. I told them what I wanted to do and that I wanted to hear what they had to say about anything in this world, the movement, or whatever.

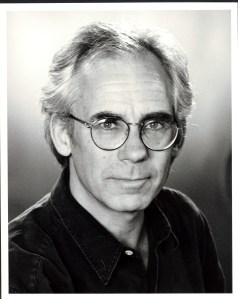

An official portrait that I scanned for Jim. Don’t know yet who to credit…

T. Campbell:

So what, what happened in a sense is that you meet one person, they would introduce you to someone else, they would introduce you to some- body else …

J. Szalapski:

Exactly. Dennis was friends with Townes and Guy they’re both very highly respected in the songwriting community. They’ve written a lot of songs, they’re very original. Once they were both interested in the film people said “Oh, you should go talk to so and so”. Since Guy and Townes were my main characters people would say “Oh well, we’re in. Count us in. You’ve got those guys, we’re in”.

Continue reading →