On July 24, 2012 I had the great pleasure to lead a question and answer session with directors Sam Fell and Chris Butler following the NBR screening of their new film ParaNorman. They are not kids but their youthful excitement and creative energy was a testament to the many years of dedication and love that each has devoted to the craft of animation. Before beginning the Q and A they were thrilled to hear about the advertising for the film I passed on 42nd street on the way to the theater. During our talk they discussed some of the more difficult technical achievements of making the film, were open and receptive to every question from myself and from the audience, and ultimately made everyone in the room sit up and appreciate the mystery and magic that movie making can be. ParaNorman A film by Chris Butler and Sam Fell Review by Thomas W. Campbell Originally published on August 17, 2012 on the National Board of Review web site. Stop-frame animation, says British director Sam Fell, is a long and complicated journey that finally pays off when life is brought to something that should not have it. Teaming with writer and co-director Chris Butler, Fell has brought energy, style and great storytelling to the screen with ParaNorman, Laika studio’s follow up to Henry Selik’s 2009 Coraline. The roots of the story go back to Butler’s childhood, in which he, like the main character in the film, was bullied by older kids. He longed for escape and finally found it in classic horror films, especially any film with zombies and other flavors of the undead. For over a decade Butler played with the premise of a boy who was “different”, mixing youthful experiences with his love of scary films before coming up with the opportunity to see his script turned into a feature length animation.ParaNorman is a wonderful mix of storytelling and technology – it has a retro feel that can be traced back to the classic animation technique of stop-frame (known as stop-motion in the U.S.) and the witty and familiar setup of the story. The story takes place in an Eastern town known as Blithe Hollow, which, like Salem, Massachusetts, has become known for infamous witch trials three centuries ago. Norman (Kodi-Smit-McPhee) is a misunderstood high school student who happens to be cursed (and blessed) with the ability to see ghosts – and the ghosts are as responsive to him as he is to them. Norman’s “difference” is established from the start.The film opens with a scene from a low-budget horror film before revealing Norman pinned in rapture in front of the television. We meet his parents, mom with an improbably large derrière and dad with a belly that gravitationally should make it impossible for him to move forward without tumbling to the floor. Both are tired of Norman’s eccentricities and just want him to be “normal”. But Norman is anything but, as we soon learn in what at first seems to be a regular stroll down the town’s main street. As the young man walks along, greeting some neighbors, being ignored by others, it is clear that he really is somewhat odd. He pauses to talk to a bit of roadkill before pressing on. Then, as he walks towards us, the camera begins a slow movement that accelerates as it swings 360 degrees around him until it lands in an over the shoulder position that finally reveals his point of view on the world. We experience life as Norman sees it – one in which the departed are sharing their “lives” in the same space as real people. And they are also sharing it with Norman – he jokes with a woman parachutist who is “just hanging around” in a tree with a broken branch through her chest, meets a peaceful hippy who must have had an overdose, and greets a tommy-gun toting gangster with cement feet. Later we will see an owl fly across screen with a six-pack plastic holder around its neck and meet a dog that has been sliced in half but still enjoys a happy jaunt around the backyard.  Three views from a display of the actual Stop-Motion puppets and sets of ParaNorman, seen at the Loews AMC on Broadway and 68th street in Manhattan during the initial release of ParaNorman. Butler has said he was also inspired by the animated television series Scooby-Doo (Where are you?), which brought together a team of very unlikely young people to fight the ghosts and monsters of the world. For his story he wanted the “team” to make sense and for the audience to believe that they could be allies. Norman is befriended by Neil (Tucker Albrizzi), a pudgy boy who is also alone and picked on by Alvin (Christopher Mintz-Plasse), a dim-witted kid who’s sole purpose in life seems to be to make Norman’s existence an unhappy one. Meanwhile his sister Courtney (Anna Kendrick) can barely believe that she has such a brother, only acknowledging him when she meets and goes gaga over Mitch (Casey Affleck), Neil’s buff older sibling. Thrown together by the unfolding curse that hangs over the town dating back to the celebrated witch trial, this is the team that will have to learn to work together or face the wrath unleashed by the walking dead. ParaNorman mines humor from a well-crafted script and inspired (and flawless) visual execution. Borrowing from the rich history of slapstick comedy, the filmmakers create a number of hilarious scenes worthy of Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin. One standout sequence involves the death of a strange old man named Mr. Prenderghast (John Goodman), a book that might contain the secret of preventing the plague of zombies, and Norman’s attempt to wrest it from the deceased man’s hands. In the town itself are many appropriately weird characters (an oppressive theater director who gets caught with beauty clay on her face when the zombies attack, a bizarrely overweight policewoman who just wants to kick some butt, a boy scout who transforms into a lethal zombie hunter) that ultimately create more trouble for Norman and his friends than do the zombies. |

Ai Weiwei, Never Sorry – Film Review

On July 19, 2012 I had the pleasure of doing a Question and Answer session with Alison Klayman following an NBR screening of her first film Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry. She was open and generous in detailing how the film was made and how complex and challenging her two and a half year experience was – including the disruption of the editing process when she learned of Weiwei’s disappearance and detention.

Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry

Directed by Alison Klayman

Film Review by Thomas W. Campbell

Originally published by the National Board of Review on July 27, 2012

Alison Klayman has skillfully portrayed the life, art, activism and downright quirky nature of Ai Weiwei, China’s leading cultural provocateur. The filmmaker met the artist around the time of the controversy surrounding the building he co-designed, which became known as the “bird’s nest”, for the 2008 Olympics in Beijing. Beginning as a small documentary of an exhibition of Weiwei’s New York City photographs (he lived on New York’s turbulent Lower East Side from 1983 to 1991), she was soon accepted into the artist’s circle and continued to document him for the next two years.

Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry is a well-told story about a man who is confrontational, controversial, and virtually unknown to many in the west. Ironically, the powerful hand of Chinese censorship means that he is even less-well known in China, at least among those not politically engaged. Weiwei’s life is a very unusual one and it is hard to think of a parallel in the west. His father, Ai Qing, was one of China’s most famous and influential poets, and Weiwei’s family enjoyed a life of privilege – until they fell afoul of the communist party. They were sent into exile in 1958 (a year after Weiwei’s birth) and forced into hard labor and other forms of “rehabilitation”, including the ritual humiliations that were cast upon the intellectual class, during Mao Tse-tung’s Cultural Revolution. The family was finally able to return to Beijing after Mao’s death in 1976 and Weiwei, not yet 20 years old, began to imagine a life for himself as an artist. After living in New York City’s East Village from 1981 to 1993, Weiwei returned to Beijing to be with his ailing father and began to question – and act upon – the challenge of being an experimental artist in the “New China”.

Klayman’s two years with Weiwei (and the year that has passed since the film’s conclusion) have been remarkably eventful – and she has documented and structured the events in a way that helps to guide the viewer through a number of complex social and political issues. The most basic and important question that the film addresses is “Who is Ai Weiwei and why should we care?” There is a temptation, supported by the publicity seeking nature of the entertainment industry, to assume that famous artists/actors/directors etc. are not really in touch with political social issues – and that when they make waves (Charlie Sheen, Mel Gibson, Lindsey Lohan) it’s simply that all publicity is good publicity. Enter the son of a famous poet in China challenging government policies and it is easy to suspect that someone is just making a name for himself to sell more artwork. Never Sorry investigates the nature of Weiwei’s character through his actions – and puts those actions into a cultural context that clarifies the issues between those who are trying to “do the right thing” and a government frightened of change. The film begins with an interview at Weiwei’s home and studio that illustrates his subtle and comical approach with a story about one of his many cats. Unlike every other cat that he has known, this one can open doors (we see it leap, pull down a handle, and leave the room). But Weiwei compares the cat to humans and points out that it does not close doors once they are opened. Is this a criticism of the cat for leaving the door open, or a commentary on how this benefits the other cats that come upon the open door and can make use of it? Like his work itself, the observation makes us wonder about intention, meaning, and the relationship of the individual (the cat) and society (the house).

Early in the film two events are documented that took place before Klayman met Weiwei: his denouncement in 2007 of the Olympic Stadium that he designed (he is furious at the forced removal of Chinese citizens as the Olympics approach) and his response to the massive 2008 earthquake in Sichuan Province that killed over 5,000 school children. In each instance the artist could have accepted reality and taken his place in the rising economic stratosphere of the Chinese art market. Instead he pretty much ensures his own economic disaster by directly challenging the government. The earthquake exposed defective building practices (which became known as “tofu construction”) leading to the collapse of thousands of government buildings – including many schools. The government refused to give the names or numbers of the dead so Weiwei created an art project, with numerous volunteers, which began painstaking research to collect and catalog the names and birthrates of every dead student. Using her own interviews and clips from documentaries that Weiwei created, Klayman chronicles the degree that Weiwei will go, when pushed, to bring the truth to light.

Continue reading

Waiting for the Dark Knight to Rise – Film Reviews

Only a few days until The Dark Knight trilogy concludes – until then here are some recollections on a few films from the past couple of months.

Film Reviews by Thomas W. Campbell

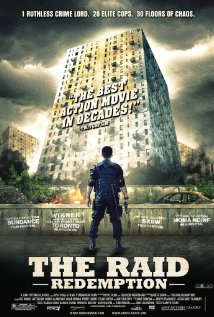

The Raid: Redemption

Directed by Gareth Evans

The National Board of Review screened The Raid to members on March 23. I had the pleasure to do a Q and A with director Gareth Evans after the screening. Evans is a young (under 30) Welch director who went to Indonesia to study martial arts, was exposed to Pencak Silat, a traditional fighting style, and made the martial arts film Merantau in 2009. The Raid (“Redemption was added to distinguish the film from other “Raids“). Both films star Silat martial artist Iko Uwais, who plays a young man leaving his village for the dangers of urban life in Merantau, and a Swat team member fighting a vicious gang in The Raid. Evans was incredibly open and enthusiastic about his work as a director – to a degree that is rare and quite refreshing. His discussion of a certain stunt gone wrong in the film was the kind of thing that would send shivers down the spines of lawyers for any major film studio.

The Raid is a must-see film for anyone with an interest in martial art films – it is essentially a police versus crazy gang in an enclosed location story (the police execute an ill-planned raid on a public housing building infested with an army of drug users and a angry and determined drug lord). The film plays around and unending sequence of action scenes – most featuring Iko Uwais, who is essentially in a continuous life and death fight. The only exception is a brief interlude, a momentary lull in the eye of the storm with his estranged brother. Uwais does all of his own stunts – some of the most incredible fighting occurs between him and Yayan Ruhian, who plays the ultimate antagonist. Ruhian is a drug soldier known only as “Mad Dog”, a wild man who refuses a gun when offered because he literally delights in the physical sensation of breaking his victim’s necks. Ruhian also worked with Uwais as co- fight choreographers for the entire film. If you can find The Raid still playing in a theater don’t hesitate. Evans is already working on a follow-up, which thankfully won’t be called The Raid 2 (It is named Berandal).

The Lucky One

Directed by Scott Hicks

The NBR screened The Lucky One on April 19 for members, students and guests and I had the good fortune to do a Q and A with director Scott Hicks after the screening. Hicks has made a documentary about Philip Glass, directed Snow Falling on Cedars with Ethan Hawke and Max Von Sydow in 1999 and, most famously, Shine (1996) a real life story centered around the talented and eccentric pianist David Helfgott. It’s a film fixated on the odd and emotionally engaging talents of Geoffrie Rush. Hicks is lean, soft spoken, has shoulder length blond-grey hair, and is quite relaxed and thoughtful.

I try to prepare for meeting and talking with directors, (and to some extent actors), by reading the source material that the films are based on. If a film is not an original script then it is most likely adapted from a story – either a novel or a short. I am alway curious about story telling decisions and love to compare the novel (starting place) to the script/film that is made from it. With Almodovar I was able to find a copy of the source text for his film The Skin I Live in. It is a very creepy French novella called (in translation) Tarantula, by Thierry Jonquet. Knowing the original text made it possible to identify the key moments when Almodovar made the story his own and to explore the adaptation process in a thorough way.

The Lucky One is based on a novel by the successful and popular writer Nicholas Sparks. My exposure to him was through a number of the film students – all girls -, at one of the Universities where I teach. For writing assignments there were students each semester who felt compelled to choose The Notebook, based on Sparks novel about a man trying to get through to his wife, who suffers from progressive alzheimer’s disease. I can visualize each scene in my mind, though I have never seen the film, thanks to the many students each semester who feel compelled to take on this melodramatic romantic touchstone of a film.

Published in 2008, The Lucky One is a novel that is an all-too-predictable potboiler that is also quite successful in bringing a tear to the eye and a flutter to the heart. Logan, an American soldier, in Iraq feels that something is keeping him alive – and decides that the talisman is a photo of a beautiful young woman from somewhere in America. He returns to the states to hunt her down and runs into a bad sheriff, who happens to be the ex-husband of Beth, the woman in the picture. You can imagine the possibilities.

Hicks makes the best film possible from the source material – keeping the basic story intact and adding a few nice twists (for instance he heightens the narrative weight of the photograph by building a secondary story from Logan’s war days around it). Hicks is great with actors (Rush in Shine, for instance) and gets everything he can from cast, crew and locations (shot in New Orleans). Zac Efron is passable as Logan – but seems to be miscast. In the novel the character has very long hair that is always falling across his face, for instance. For a soldier who has been through three duties Efron seems a bit young and maybe too much together to be believable. Blythe Danner is great as the mom figure but the performance that really stands out is Taylor Shilling as Beth, the image in the photograph. Shilling displays a range of emotions that seems realistic and impressive. At the extremes, in her pleasure to see Logan and in her despair as she confronts her former husband, Shilling has a Jessica Lange like quality that is radiant and fun to watch.

Peace, Love, and Misunderstanding

Directed by Bruce Beresford

Following the June 7th NBR screening of Peace, Love and Misunderstanding I moderated a discussion with Jane Fonda, the film’s star. Fonda was her gritty and elegant self as Grace in the film and in person, discussing not only her relationship with co-stars Catherine Keener, Elizabeth Olsen, and Jeffrey Dean Morgan but also her collaboration with Beresford. Fonda also took some time to look back to discuss acting with Marlon Brando and Vanessa Redgrave.

Peace, Love, and Misunderstanding is a somewhat too nice film by Bruce Beresford, who has directed such exceptional work as Breaker Morant (1980), Tender Mercies (1983), Driving Miss Daisy (1989) and Mao’s Last Dancer (2009). Peace, Love, and Misunderstanding makes great use of Woodstock, New York locations and real-life characters but – except for a plot line that follow the strained relationship between Grace and Diane (Keener), her onscreen daughter, and some bits about new found love between the younger actors there is little conflict or action. Still, there are fun moments and the film is probably better watched under the influence of something other than popcorn. Beresford is known for his strong work with actors and none in the film benefit more than Elizabeth Olsen, in a performance that predates her breakout role as title character in 2011’s Martha Marcy May Marlene. It’s a role that allows Olsen access into the professional world of a veteran director and some serious actors. She gives a fresh acting performance that stands out in an otherwise unengaging and light-weight film.

To Rome with Love

Directed by Woody Allen

On June 19, following an NBR screening of Woody Allen’s new film To Rome with Love, I moderated a discussion with actresses Penelope Cruz, Greta Gerwig and Ellen Page.

Woody Allen – you love him or you don’t love him (“don’t love” is often, it seems, with a passion). Regardless of opinion, on a purely objective basis it’s hard to argue against the talents of someone who has been Oscar nominated fifteen times for best screenplay and six times for best director. And, for Annie Hall, he also picked up a best actor nod. And four shiny gold statues along the way. That’s a lot of accolade and hardware for a funny little guy from Brooklyn.

Allen’s film track record has been exceptional of late, with the emotional and funny Vicky Christina Barcelona (2008), the cerebral Midnight in Paris (2011) and what feels like a collection of short stories come to life that is To Rome with Love. Whatever Works (2009) is a bit creeky, but features Larry David doing his best Woody Allen bit – and remaining mostly like Larry David. You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger (2010) didn’t work as well – the story of a writer (James Brolin) and his wife (Naomi Watts) struggling for money, while an older generation (Anthony Hopkins and Gemma Jones) struggle with divorce, loss and making fools of themselves. Still, three and a half good films out of five is not so bad.

With To Rome with Love Allen has wrapped four stories of love – sometimes for people, sometimes for ideas – in a beautiful and varied Italian envelope, brought together a skilled and accomplished international cast, and given us a ticket to one of his supremely Allenesque tales of misunderstanding and misadventure.

There are no intertwining of destinies here – characters do not suddenly appear in a tale they did not start in. The stories are intercut as they progress and each follow their own narrative arcs. Though unnamed, I will call them The Mistaken Prostitute, The Unlikely Singer, Revisiting Love, and The Price of Fame. Although the writing quality of the four stories varies a bit (Price of Fame, absurd and intimate at the same time, is the best written, whereas Mistaken Prostitute dips slightly because of a believability factor involving the separation of the two characters). Allen polishes each section of the film with his directing, location choices and, most helpfully, his inspired casting. Roberto Benigni was born to play the perplexed ordinary man who is thrust – for no apparent reason – into the role of national celebrity. Penelope Cruz, as the prostitute who must play, in a twist of fate, the fiancé of a young boy from the Italian countryside, has fun with the role by implementing all the ways she can be helpful and supportive to the befuddled boy in front of his family. The prostitute as friend and supporter. Judy Davis plays Woody Allen’s put upon and begrudgingly faithful wife in the Unlikely Singer story. Allen’s character, a retired experimental opera producer, struggles to find a way to exploit the talents of a man (real-life opera star Fabio Armiliato) who can belt out a powerful and moving aria – but only while taking a shower. In the Revisiting Love sequence Alec Baldwin returns to Rome, where he frolicked as a youth and, in a bit of fantasy reminiscent of the time traveling in Midnight in Paris, encounters a young man and two women (Jesse Eisenberg, Ellen Page and Greta Gerwin) who seem to be reliving a potentially painful moment from his own past.

Hovering on the edge of their lives, seen only by Eisenberg, Baldwin tries to convince the younger man not to fall into the same love trap that he did. During the shoot neither Page nor Gerwin knew why Baldwin appeared in scenes but did not interact with them – relying on their trust for Allen as a director to get them through each scene.

A close friend said after the screening that Allen could have shot most of the film in any setting and the stories would have worked with little change in the writing. It’s true, but I really like to experience what it’s like to take a bit of New York, in the form of recognizably befuddled characters and situations from the mind of one of New York great filmmakers, and see how everything plays out when visually transplanted overseas. It’s a treat for a New Yorker who doesn’t get out of his apartment enough.

Hysteria – Film Review

I had the pleasure of moderating a Q and A with director Tanya Wexler and actors Jonathan Pryce and Hugh Dancy, after a recent screening of Hysteria for members of the NBR. Pryce was to open at BAM in the title role of Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker on that very evening (NBR often screens in the morning) and Wexler had just arrived the evening before from a film premier in San Francisco.

Hysteria

A film by Tanya Wexler

Review by Thomas W. Campbell

Originally published on May 18, 2012 on the website of The National Board of Review

Hysteria is a film that answers the age old question–what would happen if you made a film in the style of classic BBC Victorian dramas and mixed in the true story of the fortuitous discovery of the hand held self-massage tool commonly known as the vibrator? The answer, in the hands of filmmaker Tanya Wexler, is a great deal of fun for all concerned. She has constructed a film around an obscure historical event that is one part costume drama (set in Victorian England), one part romantic comedy (a young doctor caught between beautiful sisters who are polar opposites in temperament and politics) and one part astute social and political commentary.

The script, with a screenplay by Stephen Dyer and Jonah Lisa Dyer, crafts clearly drawn characters that fit perfectly into the conventions of the romantic comedy. The casting, and Wexler’s deft directing ability, bring characters to life that is comical, likable, and fun. Maggie Gyllenhaal’s performance as Charlotte, a ball-of-energy social reformer who has dedicated her life to helping the poor by founding a fledgling woman’s suffragette movement, is the force of change that flows through the film, influencing all she comes into contact with. Gyllenhaal is “on” in almost every moment of screen time–her eyes radiant, her posture defiant, ready for any challenge to the funding of her clinic for the indigent. Felicity Jones plays her sister Emily, a polar opposite who follows her father’s dreams of wealth and living within the conventions of upper class society. But her father isn’t conventional in all ways. Played with a strict sense of propriety by Jonathan Pryce, Dr. Dalrymple has built a booming business releasing the hysterical symptoms of upper class women by masturbating them with clinical precision and the utmost detachment.

Unable to accept the standards of Victorian medical practice (bloodletting, the use of medicinal leeches, lack of cleanliness towards patients), Mortimer Granville, played by Hugh Dancy, is injected into the Dalrymple’s lives when he accepts a position assisting the father’s hysteria-abetting treatments. As befits the genre, young Granville is rewarded the proper Emily for his hard work at the clinic but ultimately finds himself drawn to the less conventional free-spirit Charlotte. Helping Granville along the way is Rupert Everett’s Edmund St. John-Smythe, who is quite gay, an eccentric inventor (creating a working telephone prototype and the world’s first electric powered feather duster simultaneously), and has the deep pockets necessary to support both lifestyles.

There is no real surprise in the way the conflicts and personal relationships play out, which is part of the film’s pleasure. Genres have conventions and comedies are built to satisfy our cravings for these rules to follow through to their expected conclusions. When Charlotte’s independence finally leads to her arrest and trial, it comes as no shock that Granville will be forced to decide between his allegiance to her father (and the trappings of success he offers) and his mounting admirations for her. Formulaic as the moment seems, the result still manages to engage our intellect (we’ve seen the roots of Granville’s decision take hold in his earlier actions) and our emotions (the penalties faced by Charlotte were cruel yet quite realistic).

Hysteria works as an historical comedy – the script, acting, cinematography (Sean Bobbitt previously shot Steve McQueen’s Hunger and Shame) and editing are well crafted. But the film has the added complexity of social commentary and is much more than a one-joke affair. It is ultimately a story of female empowerment, told through the development of technology. The inspiration for the vibrator comes about through the necessity of compensating for injury (hands can only be used to “remedy” the female body for so long). But the creation of the vibrator for medicinal purposes, as revealed through Wexler’s storytelling, is only the beginning of a process that cannot be stopped. Once removed from the hands of the (male) doctors–through the advent of battery powered portable devices–the vibrator offered the potential for women to seek their own “remedies”. Furthermore, its use need no longer be restricted to the scientific function of “hysteria release”. Women could finally, on their own schedules, let their hair down and have some fun. Echoing Freud’s yet to be uttered words, Dr. Dalrymple explains to Granville (while treating a patient) that there is no pleasure to be derived in the process of stimulating the external body–only remedy. A woman, he solemnly reveals, can only achieve pleasure from being penetrated by a man. As Hysteria reveals, it sometimes takes the invention of a new technology to show us the error of our ways.

Polisse – Film Review

Polisse

A film by Maïwenn

Review by Thomas W. Campbell

Originally published on May 18, 2012 on the website of The National Board of Review

The novel spelling of the word Polisse, the new film by actress/director Maïwenn (The Actress’ Ball), appears in the opening credits as though scrawled in a child’s hand with crayons. Which is appropriate for a film inspired by the French CPU (Child Protection Unit) – a branch of the police force which investigates child abuse (and worse). The film is remarkable on many levels, taking on a television police/detective show format and inverting it in a compelling way. Convention dictates an investigation that follows only a few storylines (usually one central story and one or two tangential ones). The structure will come from the interaction between the investigators and the suspects, culminating in the inevitable collision of the two forces. Maïwenn and her cowriter Emmanuelle Bercot have come up with an approach that feels realistic in a documentary way and exciting in terms of character development – and is closer in spirit to war films such as Full Metal Jacket and The Thin Red Line than the police genre. In Polisse viewers are immersed into the lives of a team of professionals and follow them, individually and as a group, as they struggle with the daily grind of child abuse cases – and confront the emotional and psychological toll it takes.

The investigators are individualized and full of interesting character traits (and flaws). They are a mix of men and women, each with outgoing personalities and passionate attachments to their work. Iris, a natural leader (played by Marina Foïs) is obsessed with her weight, demanding of her husband for a child, and naturally controlling of those around her. Nadine, played by Karin Viard, is caught on the short end of a bad marriage and also enmeshed in Iris’s influence. Fred, (played by Joey Starr, who has worked previously with Maïwenn), is a strong Alpha type with a young daughter, a failed marriage, and an initial dislike and inevitable attraction to Melissa (played by Maïwenn). Emmanuelle Bercot plays Chrys, a tough professional who also happens to be a lesbian. The power of the film comes from the strength of the ensemble – they work hard, with respect and professionalism, and play hard as well.

The narrative is bolstered by the inclusion of Melissa, a photographer who is embedded into the unit by her well-connected former husband. She is tall and beautiful in a Bianca Jagger sort of way but hides her elegance behind tied up hair and black oversized Clark Kent style glasses. She is a mousy time bomb ready to go off, whether through the effect of her beauty or her relentless documentation of the investigative unit.

The cases taken on by the CPU are especially troubling because they involve children placed in dangerous and threatening situations, often involving relatives and family friends. We meet children who suffer at the hands of bad mothers (one woman is taken in when she is caught violently shaking her baby, only to reveal that she is casually molesting her young son), upper class fathers (a young girl is being abused by her father, who feels immune to prosecution because of his connections), unfortunate immigrant mothers (a woman struggles with the reality that she must surrender her son for financial reasons), wicked grandfathers, and even their own adolescent peers. The effect on the investigators – and on the audience – is cumulative and deep.

Continue reading

Where the Wild Things Are – Film Review

Where the Wild Things Are

A film by Spike Jonze based on the book by Maurice Sendak

Review by Thomas W. Campbell

Originally published on October 16, 2009 on the website of The National Board of Review

Where the Wild Things Are is an exciting and vigorous adaptation of the seminal book by Maurice Sendak. Unlike most film versions of literary material, there are few subplots to alter or characters to drop. One of the most engaging things about the book is the power of its simplicity. There is little that could be subtracted from the story without harming the narrative. The question of adaptation becomes: how do you keep the spirit alive while expanding the narrative to fit the necessary screen time?

Director Spike Jonze (Being John Malkovich, Adaptation) has added his own signature to the story and created a remarkable cinematic equivalent to the book, expanding the adventure in a strange world in ways that feel both familiar and at times unexpected. Jonze, who has said that it took him years to discover a way to bring the story to the screen, has found the key to adaptation in the action-oriented personality of young Max. Adding a framing story that involves an ice igloo to Max’s waking life, he creates a parallel event on the island that develops into an elaborate extension of Max’s keen imagination. The result is a tale that might have existed between the original pages of Sendak’s slim and engaging book, if he had elaborated further upon his own creation.

Played with authority by first-time actor Max Records, Max is a startling bundle of youthful aggression and determined adventurism. From the opening sequence we sense that he has more energy pounding inside him than can be controlled. Pursued by a frantic hand-held camera down a wooden staircase, clutching a very disturbing fork, he races in full flight after a terrified gray poodle, wrestles the animal to the floor, and lets out a loud animal roar. Max arrives fully formed – a screaming ball of fury.

Catherine Keener plays Max’s mom with a combination of vulnerability and determination that is truly remarkable. Struggling with work and the promise of a new relationship, even she has to throw up her arms when Max, in his wolf suit, wrestles her to the ground and sinks his teeth into her shoulder.

The heart of the film is the journey that Max takes into his own imagination. Unlike the bedroom/jungle transformation in Sendak’s book, Jonze releases Max into the streets as though he were a beast propelled from a cage. He flees his home with abandon, finally commandeering a small sailboat that takes him on an overnight journey to the mysterious island where the wild creatures live. Sendak’s characters, voiced by a cast that includes James Gandolfini (Carol), Catherine O’Hara, and Forest Whitaker, come alive in a nighttime encounter. Max confronts Carol, the big furry alpha male who parallels his own aggression and insecurities, and is recognized as a similar soul.

The integration of physical puppets, animated by the actors working inside them (designed by the Jim Henson group), and 3D animation is subtle and blends seamlessly. Max’s “friends” are big, live versions of Sendak’s creations, with grace and tons of personality. The music, composed by Carter Burwell and Nancy O., is youthful, upbeat, and infectious, and works brilliantly with the brisk but carefully paced editing.

Jonze has created fully developed characters with their own mannerisms, physical characteristics, and ability/desire to verbalize. The much-expanded dialogue, designed to individualize the characters, might cause unease for some who have truly internalized the book. When you read Where The Wild Things Are, the large detailed drawings and spare narrative encourage you linger on each page, to meditate on form and meaning, to add your own sounds and action to each frame. But the process of adaptation means that the imagined must somehow become concrete.

Where The Wild Things Are is a joyful and serious reflection on childhood dreams that exists somewhere between the innocence of youth and the awakening of adulthood. It’s an honest and emotionally engaging adaptation of a truly influential work of art.

The Deep Blue Sea – Film Review

The Deep Blue Sea

Directed by Terence Davies

Review by Thomas W. Campbell

Originally published on April 17, 2012 on the website of The National Board of Review

The Deep Blue Sea, the new film by Terence Davies (Of Time and the City, House of Mirth), is an adaptation of the 1952 play by Terence Rattigan. It is the story of an obsessive and depressed woman named Hester (Rachel Weisz) who leaves her marriage with Sir William Collyer, a wealthy and respectable older man (Simon Russell Beale) for the arms of Freddie, (Tom Hiddleston), her younger lover, an erratic playboy without means to support her. The plot begins with a suicide attempt by Hester then plunges us into the despair and fear of a woman desperate for the love of a man incapable and unwilling to give her what she wants–love and sex.

There is an austere beauty to the world of 1950 England that Davies creates for the screen. His previous film, 2008’s Of Time and the City, was his first documentary and created a very personal vision of Liverpool, England, his home town. The world of The Deep Blue Sea is awash in muted colors and great design. The vintage middle class wardrobe of the young pub crawlers who Hester spends time with, the wealthy elegance of tuxedos and gowns which represent the society Collyer moves in, the opulent mansion and classic British luxury car, the dark contrasted with the monochrome sepia of the flat that Hester has “stepped down” to. The effect is to transport one to an England that feels nostalgic and somewhat hyper-realistic. Much of the film’s pleasure comes from the highly detailed set design and the high contrast and deep saturation of the image–often presented in a palette highlighting earthy browns and greens, especially in the flat where Hester attempts suicide. Equally effective are the the physical details, almost incomprehensible to a modern audience, specifically defining time and place. In the suicide sequence that opens the film, Hester struggles with coins, dropping them with large kerplunks into (we finally realize) a meter device that must be fed to provide the gas that heats the apartment. A relic of early 20th century design, the tiny spouts of the peculiar shaped ceramic-faced unit come to life as they belch invisible and deadly gas.

Unfortunately the visual strength of The Deep Blue Sea, inspired by a love for the England of previous generations, can not mask the film’s deep flaws. Davies has saddled himself with a dated and extremely cumbersome script. The dialogue, especially when Hester is with her husband and/or her mother-in-law, feels creaky and literal–a raised eyebrow away from parody. An example occurs when, only moments after Freddie has just stormed away from Hester, Collyer is at the door. They have a rambling conversation that finally concludes with Hester expressing her desire to experience lust (with Freddie), while Sir William Collyer chooses to forego desire. Though sounding vaguely feminist at this moment, Hester is a miserable failure because she wastes her life begging for the attentions of a man who does not love her. If there is a best line in the film it is delivered by a secondary character–an older man who is an informal doctor. When he is challenged by Collyer, the somewhat scruffy man becomes offended and says “I give my respect to those who’ve earned it–to every one else I’m civil.”

Continue reading

Being Flynn – Film Review

I did a Q and A on February 28 with Director Paul Weitz and Co-star Paul Dano following the pre-release screening of Being Flynn for members of the National Board Review. We enjoyed discussing the adaptation of Nick Flynn’s complex memoir “Another Bullshit Night in Suck City” and the ways that the cast worked together to develop the boldly crafted characters from the book.

Originally published on March 2nd on the website of The National Board of Review

Being Flynn

A film by Paul Weitz

Review by Thomas W. Campbell

Paul Weitz has a touch for comedy – his previous films include the franchise establishing American Pie (with his brother Chris), About a Boy, an adaptation which brought him a co-writer Academy Award screenplay nomination, and a perfectly adequate continuation of the Ben Stiller/Robert De Niro Meet the Parents series (Little Fockers). Being Flynn, his latest film, which he also wrote, is based on the novel “Another Bullshit Night in Suck City: A Memoir” – a complex, emotionally gripping and decidedly unfunny story. Why did Wietz make such a genre leaping commitment to a story so different in style from his previous work? And in doing so how did he manage to nail it so perfectly, to transform a book with almost no dialogue based around a painful relationship of loss and betrayal into a film that engages from start to finish?

Being Flynn is a deft adaptation of a sprawling, non-linear memoir about abandonment, self-doubt, and loneliness. It’s an emotionally challenging story about a young man named Nick Flynn, abandoned in youth by his father, left to cope with his mother’s suicide, alone without anyone to point him towards answers – or even useful questions. Working in a homeless shelter as he tries to sort out his own issues, Nick is abruptly confronted with his fathers reappearance after 18 years of silence. Angry and confused, Nick is determined to prove that he has no need for reconciliation. Weitz uses a narrative technique he honed in About a Boy, which begins with alternating scenes narrated by the bachelor (Hugh Grant) and the boy of the film (Nicholas Holt). Being Flynn pushes the dual narrative concept even further. As we meet Jonathan Flynn (Robert De Niro) going about his business as a cab driver we hear De Niro’s unmistakable voice announce that he is one of the world’s greatest writers. Not a good writer, one of the greatest. Such bravado, immediately belied by the circumstances of his work, is wonderfully Rupert Pupkin like in self aggrandizement, and also harks back to the attitude that of another taxi driver he once played. As we wonder whether to laugh or cry the film cuts to a Nick Flynn (Paul Dano), a young man scribbling frantically on a yellow pad late in the night. His voice over tells us this is not his father’s story, it is his own. From the opening moments the film is about trying to understand why father and son have gotten to where they are – it engages us early with the mystery of the past and a spiraling-down present day action.

This is serious stuff, denser and more dangerous than any of Weitz’s previous work and seemingly an abrupt stretch coming off his recent entry in the Focker series. But Weitz nails it – his adaptation of the novel is clear, poignant, funny and emotionally compelling. Hardly new to the material, Weitz has been attached to the book since first reading it in 2004, shortly after it was published. The true story he encountered – about a fragmented and disturbing father/son relationship – troubled and fascinated him. He saw echoes of his own relationship with his father and was attracted to the complexity of the narrative. It took about eight years, a number of possible studios, and according to his own count, thirty drafts of the screenplay until finally being able to decode the tale into a film script that both he and novelist Nick Flynn felt ready to proceed with.

Filmmaker Interview – John Korty

Featured

In the winter of 1988 I had the pleasure of doing a phone interview with San Francisco based filmmaker John Korty. I conducted the interview for The Off-Hollywood Report (then known as the Magazine of the Independent Feature Project). I was pleased to see it published in the March issue of that year and am reprinting the last part of the interview below. Korty was a wonderful person to talk with and our conversation went much longer that either of us probably thought it would. I think the magazine agreed to cover any phone charges so we just burned a lot of cassette audio tape.

T. Campbell: …Jumping ahead a bit. Twice Upon A Time is an animated film you made for the Ladd Company and George Lucas, You used a technique called Lumage, which is the use of cutouts and a method of animating the cutouts. Tell us something about this animation technique and your experience after completing the film.

J. Korty: I developed the Lumage technique over almost 20 years of animating because I couldn‘t stand cell animation and felt there must be a better way. We did Sesame Street spots and I‘d made a short before The Crazy Quilt that was nominated for an Oscar called Breaking the Habit. The making of Twice Upon a Time is a very complex story. It was an independent film to the extent that we raised some money independently to develop it and the money was supposed to go into a screenplay and a sample reel. Originally, it was going to be three or four minutes of animation, As we went along, we felt the sample was more important than a completed screenplay so we changed it to a kind of treatment and a 10 minute reel. lt took one-and-a-half years to do that much. I had known George Lucas for several years and thought “We might as well start here.” and we had a screening with George. He arranged a meeting in L.A. with The Ladd Company. We talked for a while, and within a month or two had a production deal.

T. Campbell: At the time there were other animators, like Ralph Bakshi, who were doing very well. Were you unhappy with the quality of animation you were seeing in general?

J. Korty: I‘m not really a fan of most animation. I don‘t get excited about the rounded forms or by nostalgia animation. I am more interested in modem graphics. Twice Upon a Time doesn‘t look like anybody else‘s animation.

Continue reading

A Separation – Film Review

Directed by Asghar Farhadi

Review by Thomas W. Campbell

Originally published on January 21, 2012 on the website of The National Board of Review.

A Separation is a small powerful film by director Asghar Farhadi that tells the story of personal choices faced by a family living in modern day Iran. The film has been compared to Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon, which in 1950 famously explored a murder from five perspectives, including that of a spirit. Like Kurosawa’s film A Separation is the story of how one unfortunate event affects many people but is almost exclusively restricted to the experiences of a middle class family – father, wife, grandfather and daughter. At numerous times, Farhadi, who wrote and directed, uses a very effective and somewhat unusual technique to create empathy for the family – a technique that Kurosawa exploited fully in his own film. A Separation opens with a shot that goes on for a number of minutes. Simin (played by Leila Hatami) and her husband Nader (played by Peyman Moadi) sit in a small office facing the camera, which has become the point of view of an authority figure who will decide if a divorce will be granted. She explains that she wants to take custody of their high-school-age daughter and leave Iran. He explains that his wife must stay to help take care of his sick father. The couple argue their case to the judge (and the audience) and we find ourselves thrust into the role of both judge and jury. We are in the middle of a complicated relationship between two intelligent and passionate people – and want to know more about who is “right” or “wrong”.

A Separation is an extremely well crafted screenplay that builds suspense by creating an evolving and volatile domestic situation in which something clearly has to give (there is a 40 day deadline before the visas to leave Iran expire). The situation is made all the more unbearable by the literal and metaphorical weight that hangs around the family’s shoulders – they must find a way to take care of the husband’s almost completely helpless father, who suffers from Alzheimer’s disease. I could follow the screenplay from the brilliant setup through the believable and quite organic story complications – but that would spoil the viewing for the many folks who have not seen the film yet. There is so much that is authentic and moving in the way that characters come together – specifically the way that the hiring of Razeh, a woman meant to watch Nader’s father, leads to a series of events that hurt everyone involved. The acting is strong and direct. Leila Hatami portrays Simin with a single conviction – to convince her family, and the judge, that she may leave Iran with her daughter. Peyman Moadi’s Nader – torn between his love of father and responsibilities to his wife and daughter – is a man caught between anger, compassion, and duty. He is also a mystery – it is unclear whether he is being cheap by not hiring qualified help for his father or whether he really is so short of money that this is not possible. Sarina Farhadi’s depiction of Termeh, their daughter, (in real life the daughter of director Asghar Farhadi), is in some ways the biggest revelation of the film. She embraces the character with an innocence that is clearly destined to crash against the rocks of life’s brutal and rocky waters. Her reaction shots reveal the toll that is being exacted on her like slow-drip water torture. There are no easy truths in the film, and even though we are restricted to the lives of Simin and Nader’s family we also begin to understand and appreciate the “antagonists” in the story – Razeh (Sareh Bayat), her hot-headed husband Hodjat, and their quiet daughter Somayeh (Kimia Hosseini). As the motivations of each person are revealed the meaning of “right” and “wrong” becomes more and more elusive.

The sound design of A Separation is remarkable – the complete absence of soundtrack music or audio effects of any kind offers no distance or respite from the world of the film. Without a musical score, or even motifs for characters or places, we are left completely on our own as we grapple with the acceleration of events and our feelings concerning their impact on the lives of the characters. Like Rashomon, we begin to understand a terrible event from an ever widening perspective – two couples, their children, the extended family, friends of the family, the people they work with, the authorities who hold the ultimate power of judgment. A Separation is an intensely realistic and believable interpretation of the Kafkaesque absurdities that infiltrate every level of society and culture.

Using a natural and realistic directing style, director Asghar Farhadi has found a nearly perfect way to bring his superbly written script to the screen. A Separation is a realistic story of personal struggle within the bureaucracy and religious society of Iran that also feels universal in its depiction of family conflict. The film richly deserves the still accumulating accolades it has received. It is assured and bold filmmaking – a critical success that is also selling tickets through word of mouth. Neither a heartwarming or action-oriented story – the film is essentially what the title suggests, a story about two people breaking up. Which is like saying that The Girl with a Dragon Tattoo is about a kinky relationship. There is much more going on – and the details are what make the experience so deeply rewarding.